Generally speaking, the Roman Empire is remembered for its cutthroat politics, gladiatorial games - and the roman army. For centuries Rome relied on its armed forces to both expand their empire and defend their borders and while they were not completely invincible some defeats resonated more than others. One of these happened in present-day Germany in the Teutoburg Forest in 17 B.C.

Publius Quinctilius Varus was placed at the head of Legions XVII, XVIII and XIX (17, 18 and 19, respectively). Furthermore, he had six cohorts of around 480 men - the number varied at all times. of auxiliary forces as well as cavalry. Rome was experiencing a tiresome problem in Germania with an increasing amount of rebellions amongst the local population. Usually, Varus would have more men at his disposal but recent unrest in the Balkans had obliged these to move there.

|

| Varus receiving German leaders |

Therefore, the legions that were available in 9 AD were not in the best condition. Some of the men who have been left in Germany were not used to fighting in actual battles - at most they have had experience with smaller skirmishes. The legions were also not at full capacity. Varus had sent several detachments out to perform various tasks (construction, patrols etc.) in the nearby area. This in itself was far from unusual but it was an odd choice considering how depleted the Roman forces already were.

Also, the men of the garrison had started families which meant a large number of camp followers which only slowed the army down and made them vulnerable to attack. Arminius knew that the Romans would be very difficult to defeat if they remained within their fortified garrison. Therefore, he lured them out by leading the Romans to believe that they would only be suppressing a minor rebellion.

Dio Cassio wrote that a storm had recently ravaged the forests near present-day Osnabrück which rendered the existing roads muddy and difficult to traverse. Besides, the road was very narrow which obliged Varus' men to move in a rather thin line stretching up to 20 kilometers long. The line was a mixture of soldiers, camp followers, wagons and beasts of burden. Obviously, they were extremely vulnerable in this position - and the Germans knew that. It is not unlikely that the roman forces had been shadowed by German scouts who would have known the landscape well enough to make themselves inconspicuous. Exactly how many men made up the tribal army cannot be ascertained with certainty. Spencer Tucker puts the number between 20-30.000 in his Encyclopedia of World Conflict.

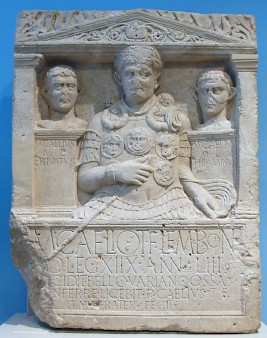

|

| Memorial for a soldier killed at Teutoburg |

The Germans attacked in a classic ambush; they surrounded the scattered roman soldiers and bombarded them with spears and javelins. Arminius led the German tribes; he was a native of Germania but had spent a good deal of his life in roman service following the failed rebellion of his father, Drusus I. This gave him invaluable information as to how a Roman general would conduct himself.

Those of the Roman soldiers who did not fall within the Teutoburg forest itself erected a semi-fortified camp in which they spent the night. The weather did not appear to have improved which made escape any easier. The following day they attempted to escape to what is now known as the Wiehen Hills but many more fell to the continued attacks from the tribes. The remaining men realised that they were in a desperate situation and made a last-ditch effort to safe themselves.

|

| Axel Thiele unearthing a mule - one of the beasts of burden used by the Romans |

Arminius had no intentions of letting his foes escape. Knowing that the only way open to the Romans was a narrow strip of sandy land between the forest and marshland, the tribes had dug trenches and erected wooden walls parallel to the road. This permitted the tribes to attack the Romans without their enemies being able to retaliate. It was not for lack of trying, though. The Romans attempted to scale the walls but were ultimately unsuccessful.

The result was complete annihilation for the Romans. Varus himself committed suicide, as did Ceionius, another commander. A less valiant end came to the Legatus Numonius Vala who attempted to escape with his cavalry but were hunted down and killed nonetheless. Not everyone succumbed instantly. Some soldiers were taken as prisoners by the germanic tribes and led back to their villages. Here, they would either be executed (Tacitus assured his readers that they were sacrificed and perhaps they were) while others became slaves. Besides the human booty, the Germans took away loads of valuable metals, materials and gold.

It has been estimated that 14.000-20.000 men were killed in the disaster of Teutoburg. The few that did manage to survive were either discreetly redeployed to other legions or discharged. It is hardly a wonder that they were traumatized by what they had experienced. Some went on to describe how the forest seemed to have come alive around them. The news sent shock waves through the Roman world. Suetonius reported that Emperor Augustus was devastated by the news and repeatedly shouted "Varus, give me back my legions!".

Varus was widely blamed by his contemporary - and later - Romans. Dio Cassio critiqued the general's choice to spread his men out instead of keeping them together which would made it far easier to assume battle formation. Usually, when the Roman army was on the march each legion's men were kept close by so that they could easily hear the signals from the trumpets. This, in turn, would mean that they would be ready to resist ambushes or go on the offensive. However, this did not happen in Teutoburg. The men were simply spread out too widely; organization was not up to the usual Roman standards.

Teutoburg served as an example for later generals. Vegetius noted that the organized marching formation was never to be broken, as it would lead to "universal disorder and confusion". Emperor Augustus was forced to reintroduced conscription by drawing lots to replace the legions that had been lost. Even so, the numbers XVII, XVIII and XIX would never be used for legions again.

Sources:

- Dio Cassio

- Great military disasters by Julian Spilsbury

- Rome's Greatest Defeat: Massacre in the Teutoburg Forest by Adrian Murdoch

- The ambush that changed history by Fergus M. Bordewich

- Battles that Changed History: An encyclopedia of world conflict by Spencer Tucker

- Compendium of Roman History by Marcus Paterculus

- The Twelve Caesars by Suetonius

- Rome in the Teutoburg Forest by James L. Venckus

- Conflicts that changed the world by Rodney Castleden

- Tacitus